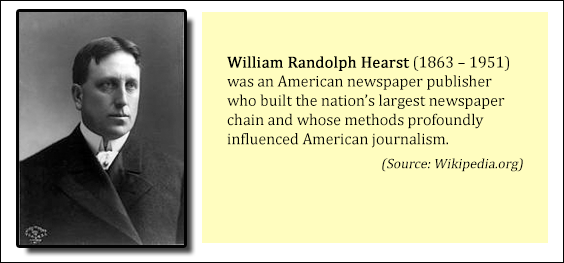

The infamous publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearstis purported to have said that the power of the press is for those who own one. He would know. As an American multimillionaire back in the 1920’s he ran 28 newspapers, published a stable of magazines including Cosmopolitan, and many books to boot. He used his printing powers to influence national elections, military interventions, and even what was going to play in the cinemas. In the monolithic era of Hearst’s world it took millions of dollars to get his opinions into print and, therefore, into the hands of millions of his readers.

The infamous publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearstis purported to have said that the power of the press is for those who own one. He would know. As an American multimillionaire back in the 1920’s he ran 28 newspapers, published a stable of magazines including Cosmopolitan, and many books to boot. He used his printing powers to influence national elections, military interventions, and even what was going to play in the cinemas. In the monolithic era of Hearst’s world it took millions of dollars to get his opinions into print and, therefore, into the hands of millions of his readers.

Up until recently it has remained prohibitively expensive for most people to have access to quality printing for their ideas. The average book produced on an offset printing press would take hours to set up (pre-press) on a machine requiring expert skills to operate in a process that wasted a lot of paper. Once the thing got humming it could print a thousand books in a matter of minutes, but this meant you had to order a thousand books (or 10,000) to make publishing cost effective. If you only wanted, say, 10 copies for a local book club or 50 for a seminar you were giving, you were out of luck.

Up until recently it has remained prohibitively expensive for most people to have access to quality printing for their ideas. The average book produced on an offset printing press would take hours to set up (pre-press) on a machine requiring expert skills to operate in a process that wasted a lot of paper. Once the thing got humming it could print a thousand books in a matter of minutes, but this meant you had to order a thousand books (or 10,000) to make publishing cost effective. If you only wanted, say, 10 copies for a local book club or 50 for a seminar you were giving, you were out of luck.

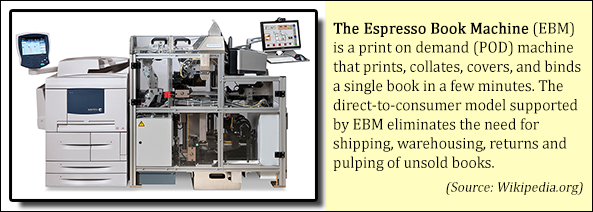

Since the dawn of Postscript software in 1982 and the resulting desktop publishing industry, this barrier of offset printing has been steadily eroding. The power of the press literally changed hands the day vector imaging software entered the fray. Within a decade just about anyone with a desktop computer and a laser printer (or access to one at a few cents a page) could publish anything they wanted. Today, a photocopier-looking device such as the Espresso Book Machine can print and bind (complete with a color cover) any book you choose from its online library in a matter of minutes.

The Power of the Press Belongs to Anyone With Technology

Printing has always been about technology, but what happened in the ’80s was dramatic for two reasons. Firstly, the costly aspects of typesetting and imaging plummeted when pre-press work shifted from hardware to software. But more importantly, all these innovations were put together to create printing on demand. Printing exactly what you want, in any quantity you want, to sell to whomever wants to buy it immediately, is now your unprecedented opportunity as a self-publisher.

How Printing On Demand Works

There are a number of companies that offer on demand printing to individuals wanting to self-publish their work. They’ve replaced offset printing with digital printing. The technology is similar to most desktop inkjet printers, only the ones at Apple or Ingram fill up a warehouse. These huge photocopier-like color printers take a computer file—usually a PDF generated by the program you wrote your book in—and use it to print either a one off-copy or 1000 books just as easily, as you like. The workflow is all software-oriented, so on a typical day these large book printers can reel off 100 different titles compared with maybe three on a traditional offset machine. Once the book is printed, the printer or publishing agency can send off five copies directly to Amazon, or 20 to your grandmother’s knitting group… again, as you like.

To illustrate printing on demand for self-publishing, let’s walk through the workflow of my latest book, The Identity Project.

First, I chose a company to print with. A lot of different groups offer different services and it’s best to match your audience and distribution needs with the scope of a provider. Blurb (similar to Apple but cheaper) does great one off photo-books. Amazon has a really helpful self-publishing service called Independent Publishing. Lulu has a similar service. However, most of these companies offer a limited reach in terms of marketing and distribution, so I set myself up as a micro-publisher with Lightning Source in order for my book to be listed in the world’s largest book catalogue and thus give me access to most bookstores and online vendors around the globe.

First, I chose a company to print with. A lot of different groups offer different services and it’s best to match your audience and distribution needs with the scope of a provider. Blurb (similar to Apple but cheaper) does great one off photo-books. Amazon has a really helpful self-publishing service called Independent Publishing. Lulu has a similar service. However, most of these companies offer a limited reach in terms of marketing and distribution, so I set myself up as a micro-publisher with Lightning Source in order for my book to be listed in the world’s largest book catalogue and thus give me access to most bookstores and online vendors around the globe.

Next, I designed the book. The design has to fit within the specifications of the printer you are working with. Most self-publishing services have limited trim sizes that you need to stick with. These sizes cover most of the standard book sizes you’ll need. You can outsource the final design to a graphic designer (and probably should, at least for your cover) but I like the art of typesetting and cover design so I did my own. If it’s a straightforward design you can most likely use your word processor, but I also recommend using a proper page layout program like Adobe InDesign.

Next, I designed the book. The design has to fit within the specifications of the printer you are working with. Most self-publishing services have limited trim sizes that you need to stick with. These sizes cover most of the standard book sizes you’ll need. You can outsource the final design to a graphic designer (and probably should, at least for your cover) but I like the art of typesetting and cover design so I did my own. If it’s a straightforward design you can most likely use your word processor, but I also recommend using a proper page layout program like Adobe InDesign.

I then delivered the book to the printer (Amazon for the Kindle version, Lighting Source for print). Each service will specify the kind of file you need to generate from your word processor or page layout program. Typically, this is a standard Adobe PDF which is pretty straightforward to create, especially if I’ve followed their trim size standards.

I then delivered the book to the printer (Amazon for the Kindle version, Lighting Source for print). Each service will specify the kind of file you need to generate from your word processor or page layout program. Typically, this is a standard Adobe PDF which is pretty straightforward to create, especially if I’ve followed their trim size standards.

Once the printer had my file they checked it for integrity (that the fonts work okay, that the trim size is correct, etc.) and then generated a proof which they sent back for me to approve. I had this proofread by an editor one final time to make sure everything was perfect. Self-publishing should never be a hack job.

Once the printer had my file they checked it for integrity (that the fonts work okay, that the trim size is correct, etc.) and then generated a proof which they sent back for me to approve. I had this proofread by an editor one final time to make sure everything was perfect. Self-publishing should never be a hack job.

After I approved the proof, Lightning Source then placed the book in their catalogue making it

After I approved the proof, Lightning Source then placed the book in their catalogue making it

available within a few days to Amazon, as well as just about every other bookstore and online shop on the planet.

Now that my book is listed, anyone can search for it online or inquire at a bookstore, place their order, and Lighting Source will print and ship it in any quantity required. Lightning Source charges the seller (Amazon or the bookstore, etc.) and then pays me directly, minus their printing costs and the retailer’s cut. Usually the retailer gets 35 to 45% of the price of the book, Lighting Source takes approximately 30% for the printing and I get the rest—about 30 to 35% of the published book price. On demand printing, coupled with easy access for book buyers via Amazon or Ingram’s catalogue, is a self-publishing coup. All you have to do is create something worth reading.

Self-Publishing in the Digital Age

You now have unprecedented options to print your work—including not printing your work at all. There are many successful authors who are going straight to ebooks and skipping the printing of their work all together.

I personally think printed books will always be superior to Kindle or iPad versions, but there are people doing really well in the digital domain. Some authors start out digital and then go to print later. RadDad is a blog that got turned into a very popular book. Same thing with Julie Powell’s blog (author of Julie and Julia, which became a book and then a film).

Blogs, Kindle ebooks, and other forms of digital communication are growing into a viable publishing format in their own right. Most of the companies listed above offer digital services (each with their own ebook formatting requirements) to make your project available on Kindle readers, iPads and many other platforms.

Like printing on demand, the ubiquitous accessibility of on-line reading or a quick download continues to simplify the process of getting your words in front of your readers. Now they just need to know you’re there. This leads us to the next article in this series: Marketing for Self-Publishing.

About the author:

Patrick Dodson is an international public speaker covering topics ranging from personal development to shifting cultural trends. Over the last four years, borrowing from his professional experience, he’s published three books: Stuff my Father Never Told Me About Relationships in 2009, Psychotic Inertia in 2010, and The Identity Project in 2011. These books are available worldwide both in print and ebook formats. He’s currently living in a cabin by a remote lake working on two new books, his second screenplay, and eating like a king (one of the books is a cookbook). Visit his website at http://www.patrickdodson.net

Patrick Dodson is an international public speaker covering topics ranging from personal development to shifting cultural trends. Over the last four years, borrowing from his professional experience, he’s published three books: Stuff my Father Never Told Me About Relationships in 2009, Psychotic Inertia in 2010, and The Identity Project in 2011. These books are available worldwide both in print and ebook formats. He’s currently living in a cabin by a remote lake working on two new books, his second screenplay, and eating like a king (one of the books is a cookbook). Visit his website at http://www.patrickdodson.net

Also by Patrick Dodson:

Part 1: The Craft of Writing for Self-Publishing

Part 2: The Craft of Editing for Self-Publishing

Part 4: The Craft of Marketing Your Self-Published Book